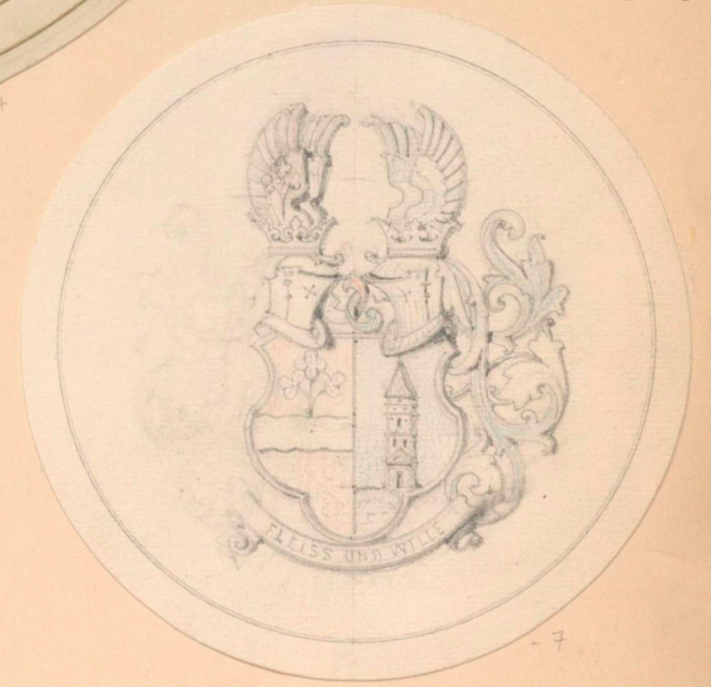

The family coat of arms originated in the course of the ennoblement into the Austrian knighthood (predicate “von Markhof”, 14.5.1872).

The coat of arms is divided into two parts. The left side shows on a red background a silver wave bar, from which three cloverleaves sprout on the common stem – one four-leaf clover, the other two 3-leaved. The clovers symbolize the four male and six female children of Adolf Ignaz Mautner. The motif was inspired by the coat of arms of his birthplace Smiřice, which also depicts three cloverleaves.

The opposite side is adorned by a square white wall tower on a blue background and green ground. Here, too, the motif can be traced back to the Bohemian roots of the family. It comes from the coat of arms of Hořice, the hometown of Julie Marcelline. It was adapted to the tower of the former church of the “St. Marx Supply House” in Vienna’s Landstrasse to commemorate the place (St. Marx Brewery) that was the starting point for the family’s success.

It is bordered by two helmets, corresponding in the colouring to the respective side of the coat of arms, which are connected by Adolf Ignaz´ motto “Fleiss und Wille” (“diligence and willpower”). He himself was and always remained mindful of the wise saying of the Greek philosopher Apollonius: “If one is poor, one must be a man. And if one is rich – human.”

Heraldry at the time of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy

Heraldry on its way through the Imperial Royal Monarchy has left behind a rich cultural legacy and was largely influenced by a central creative will emanating from the imperial royal capital and residence Vienna. The regulations of the aristocracy authority for the appearance of the coat of arms, extended over the entire territory, regardless of whether it was a coat of arms of the provinces, cities or aristocracy. The responsible officials, the coat of arms inspectors and censors of the Court Chancellery and the subsequent Imperial and Royal Ministry of the Interior, had gradually developed uniform regulations for the coat of arms, which were identical from Vorarlberg to Bukovina and from Bohemia to Bosnia-Herzegovina. Apart from the political disputes about a common national coat of arms of the Dual Monarchy from 1867, the art of the coat of arms was one of the few cultural phenomena that claimed uniform design principles across all national and religious borders. Even though the Habsburg Empire presented a nationally torn picture in the political sense, it was united and homogeneous in the heraldic sense. Although there was also something like “artistic freedom”, it was nevertheless limited. If new aristocrats (and thus also new bearers of coats of arms) wanted to realize their own ideas, it would happen repeatedly that they did not harmonize with the heraldic regulations.

Over the centuries, the coats of arms of countries and municipalities had developed on the one hand and the coats of arms of nobility on the other. The nobility titles, which had been awarded in large numbers since the 18th/19th century, formed a so-called Second Society, which at the same time created a culture of coats of arms that also increasingly fascinated the bourgeoisie. The heraldic badges were not to be excluded in the everyday appearance. Almost all buildings, monuments, carriages, livery or uniforms bore either the Habsburg coat of arms or the respective coat of arms of the nobility. No state building was erected on which the imperial coat of arms was not affixed in any way – sometimes only symbolically. When the imperial double-headed eagle opened its wings in an overwhelming way on the roof of the New Hofburg or of the War Ministry, it did not need a coat of arms shield on its chest; it was already clear what was meant. No aristocratic builder who erected a building at the turn of the century wanted to do without his coat of arms in a representative place in order to stamp his symbolic business card on the house in this way. But even the bourgeois builders, who always tried to imitate the aristocratic lifestyle, did not want to stand aside in the “heraldic hallmark” of their buildings, which is why especially the buildings erected before the First World War often carry coat-of-arms cartouches – without coats of arms – but often with the monogram of their builder. In this way, public space and general perception were permeated with heraldic symbols of all kinds.