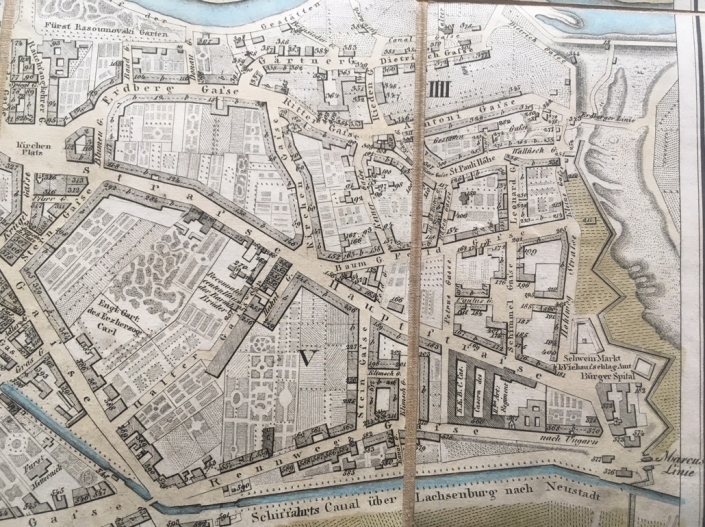

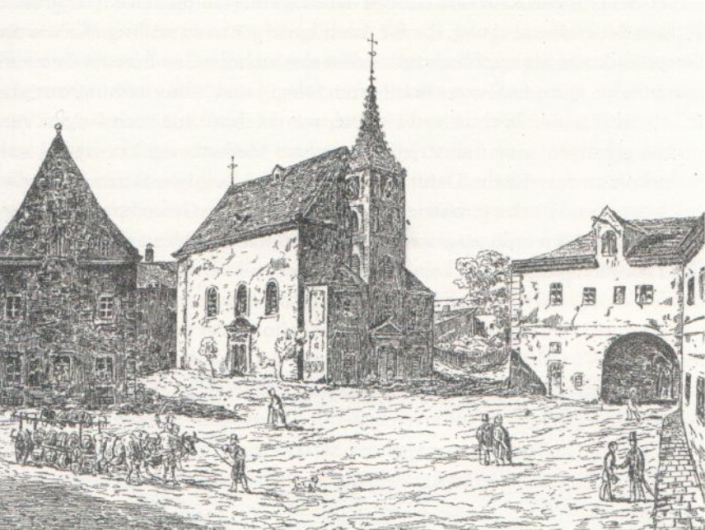

The brewery in St. Marx was one of the oldest in Vienna. They already brewed beer there in 1537 in a kind of infirmary, called ”Siechenhaus” (which was a place for lepers). The chapel of this infirmary was dedicated to St. Marcus, which later gave the name to the whole district. Over the centuries, the brewery was repeatedly leased to various, mostly unsuccessful, brewers.

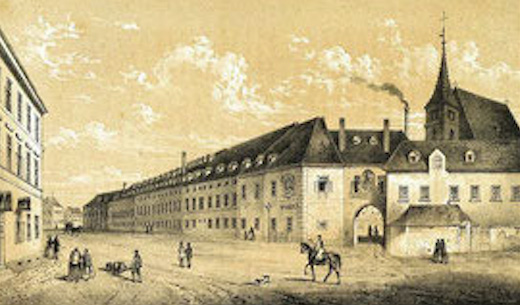

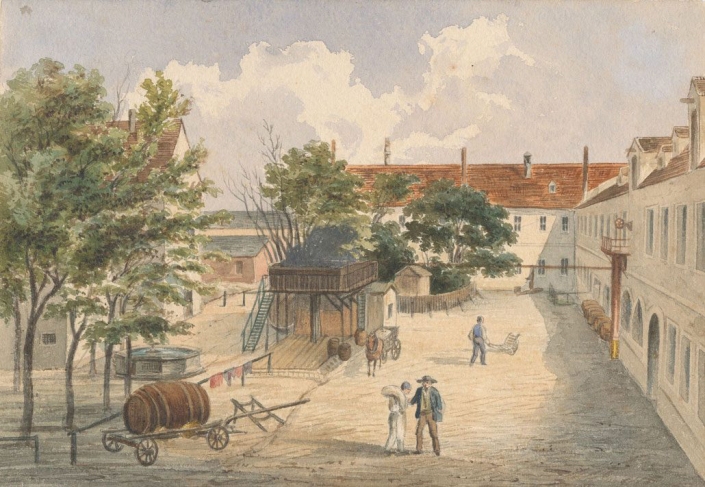

When Adolf Ignaz Mautner began to lease the hospital brewery in St. Marx in 1840, its reputation was so deteriorated that landlords were only willing to enter into a business relationship if “the beer barrels were stored at night so that customers would not know that they were being served St. Marx beer”. That is why the unique and incomparable entrepreneurial success that followed must be valued all the more highly.

At the same time as Anton Dreher (Schwechat), Adolf Ignaz began to produce exclusively bottom-fermented beer, so-called draught beer (original wort content of 9 to 10 %), which was pumped directly from the fermenting vats into the storage barrels, where it could ripen in peace and be served yeast-free. That led to large sales volumes, for example, in the Viennese Prater, where until then no chilled beer could be sold during the summer months. With his draught beer he did not only save the landlords from the problematic post-ripening process in their cellars, but he also found out that the opinion that “every beer must be damaged by severe temperature fluctuations” was completely wrong. First, he managed to preserve the beer until May by putting ice on the barrels. It was from 1843 onwards, with the construction of the “Normal Beer Storage Cellar System Mautner” (water and ice cooling devices specially constructed with serpent pipes and ice floaters ensured constant temperatures even in the warm seasons), that he was able to offer high-quality bottom-fermented draught beer throughout the summer. In that way the production of 36,000 hectolitres could be increased sevenfold from 1840 to 1875. Numerous new buildings and the use of steam power (steam engines for tapping water, malt cleaning and grinding) were necessary for that purpose.

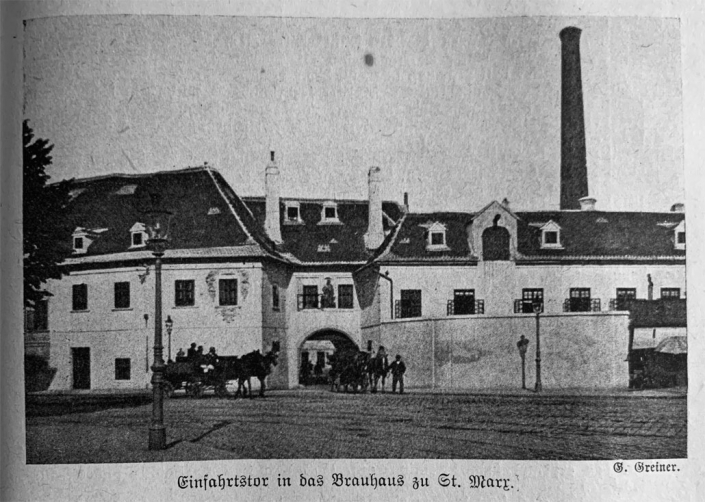

130,000 guilders of capital had to be raised in the 1850s for those investments. When Adolf Ignaz asked the hospital for a contribution of 80,000 guilders in 1857, he was instead sold the brewery “together with the brewing rights, the pub with the tavern rights, the baking house with the baking rights, the smithy, the supply house, as well as the gardens and fields”.

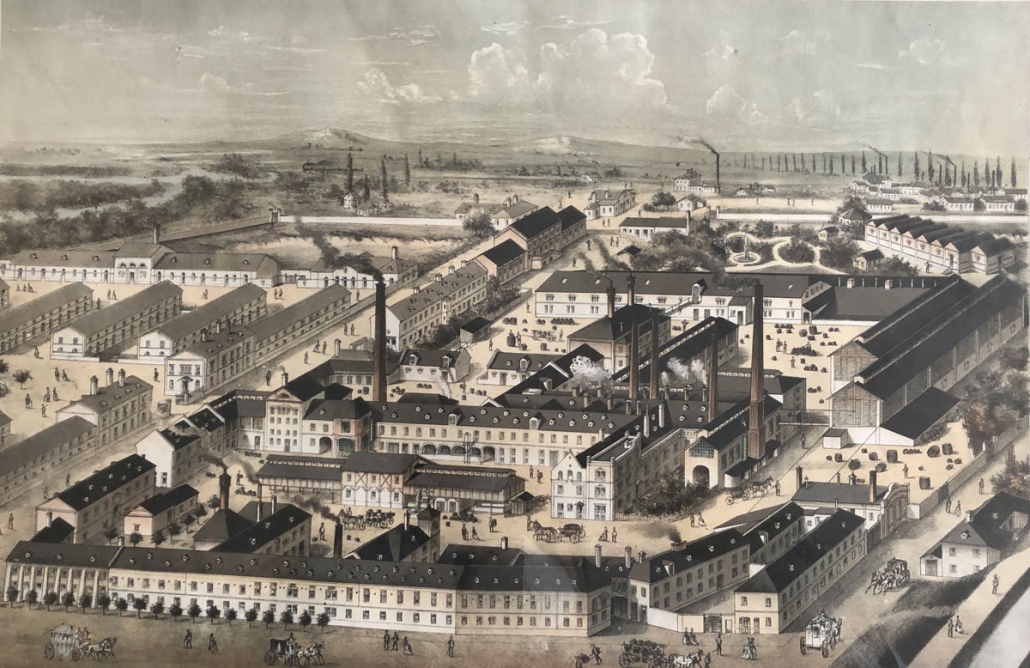

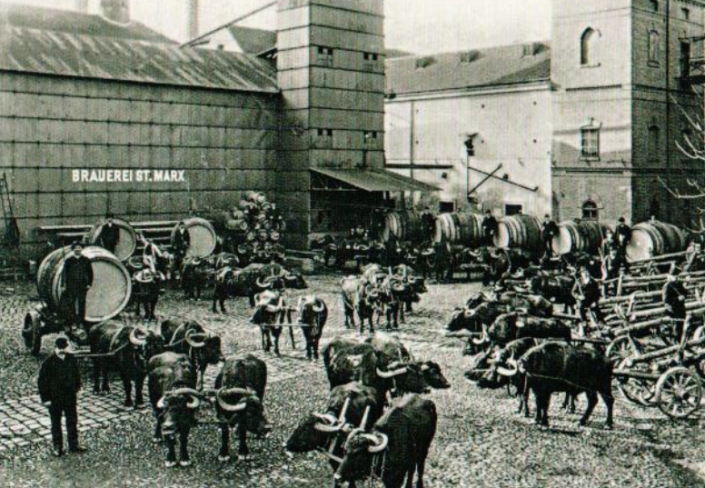

After the purchase of the brewery, the St. Marx grounds and the open country were completely rebuilt. Instead of the old hospital gardens they built stables as well as carpentry and cabinet-making workshops. In order to gain space several houses (e.g. the old smithy) were pulled down, all trees were cut down, only one old acacia remained in the middle of the courtyard. Instead of the venerable but long desecrated chapel of St. Marcus, which was rebuilt some years later almost identically on the grounds of the children’s hospital and still stands as Elisabeth Chapel near the underground station “Schlachthausgasse”, a new administration building was erected. As early as in 1860 he was running the third largest brewery on the European continent.

All this was affordable, because together with the Reininghaus brothers an innovative production method for pressed yeast had been successful, with which Adolf Ignaz won 1,000 guilders and the great gold medal of the “Bakers’ Guild” in 1850. Thus another lucrative branch of industry opened up for which factories were built in Simmering and Floridsdorf. At the 1873 World’s Fair, an impressive pavilion presented a wide range of products that had long since gone beyond beer and yeast.

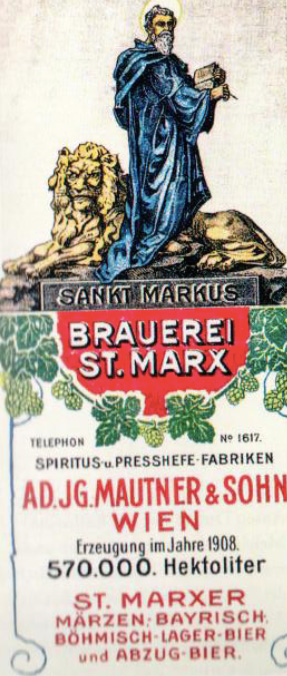

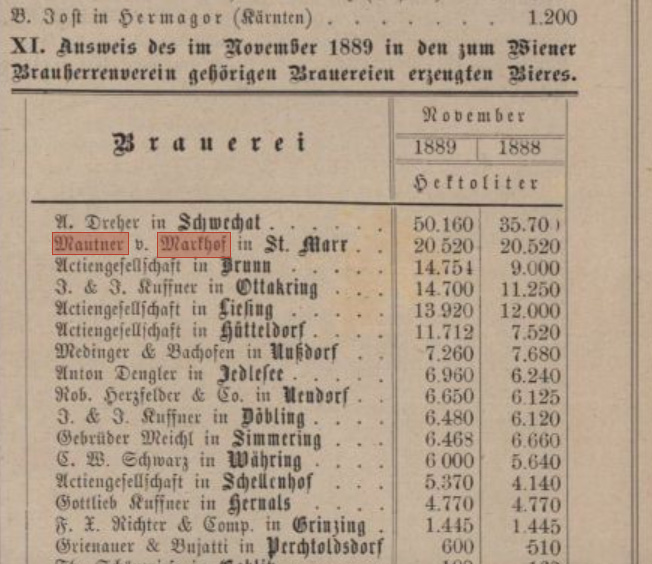

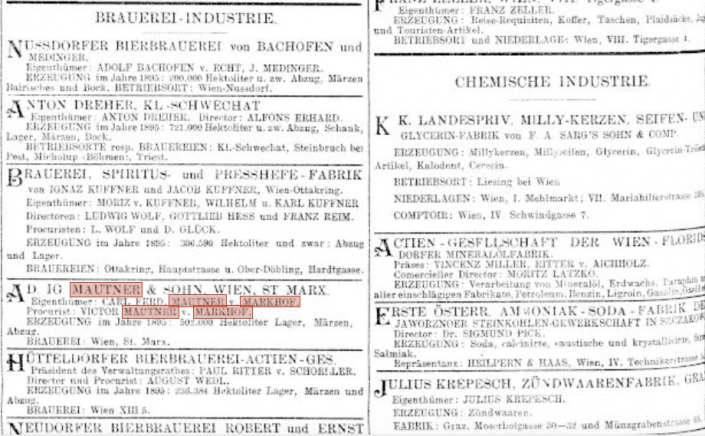

When Adolf Ignaz retired into private life for good in 1875, his eldest son Carl Ferdinand succeeded him as the new St. Marx brewer. Due to the competition with Dreher and his lager beer, he was literally forced to continuously increase production of his much cheaper draught beer. Drunk with pleasure by the workers, the market share soon reached 75 percent. St. Marx beer was also exported to Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Romania and Turkey by means of specially constructed ice wagons.

In the mid-1890s 540,690 hectolitres were brewed and 60 civil servants and 1000 workers were employed. In contrast to Dreher, in whose company frequent strikes, lockouts of workers’ representatives and hard labour disputes were on the agenda, no civil servant or worker in St. Marx was allowed to be dismissed without any particular fault on his part. It was one of the most progressive principles at that time that workers were not seen as wage slaves, but that the aim was to turn them into committed employees who felt an attachment to the company. The salary was increased with the number of years of service and at the end of the business year, bonuses were distributed according to efficiency, good leadership and merit. Extensive social benefits, such as modern bathing facilities or housing almost free of charge for workers (including heating, lighting and laundry) on the company premises, were evidence of care and appreciation. In addition to the free drink, there was also a canteen, with almost free food and drinks of good quality, for the physical well-being of those who were just as decisively involved in the overall success.

After Carl Ferdinand’s sudden death in 1896, his only son had to take over the management of the company, which in the meantime had grown to become the third largest brewery in Europe. Victor, born in 1865, was one of the most respected citizens of Vienna. As a member of the distinguished Viennese society, he received several decorations and awards from the emperor and was president of the Association of Brewers for Vienna and the surrounding area for several years. Like all industrialists of his time, he was one of the leading personalities in equestrian sports, a welcome member of the exclusive jockey club and once won the important Vienna Trotter Derby with his horses. Despite the enormous economic success of the company, Victor also had to face great financial challenges. Not only was his lifestyle expensive and his many charitable activities generous, but the inheritance also had to be paid out to his nine sisters.

In 1913, the company merged – understandably from an economic point of view – with the Anton Dreher company, which also included the Simmeringer Brewery of the Meichl family (Theodor Meichl was the father-in-law of Carl Anton Dreher). Victor was then Vice President of the newly established United Breweries Schwechat, St. Marx, Simmering – Dreher, Mautner, Meichl A.G.

St. Marx, however, should later play no further role. In 1916, three years before Victor’s death, the brewery was closed down due to rationalization measures. The factory was so badly damaged by bombs in 1945 that it had to be completely demolished. Today there is a residential complex of the municipality of Vienna, the “Madersbergerhof”, completed in 1956. The extensive storage and ice cellars, however, which were used for armaments production during the Second World War under the code name “Maria”, are still preserved under the so-called “Stadtwildnis” (city wilderness).